Born in St. Thomas, Ontario, Mitchell Frederick Hepburn attended school in Elgin County and hoped to become a lawyer. His formal education ended abruptly, however, when someone threw an apple at a visiting dignitary, Sir Adam Beck, and knocked his silk top hat off his head. Hepburn was accused of the deed and denied it but refused to identify the culprit. Refusing to apologize, he walked out of his high school and obtained a job as a bank clerk at the Canadian Bank of Commerce where he worked from 1913 to 1917. He eventually became an accountant at the bank’s Winnipeg branch.

At the outbreak of World War I, Hepburn had already enlisted in the 34th Fort Garry Horse but was unable to obtain his parents’ consent to sign up for the Canadian Expeditionary Force. He then became a lieutenant in the 25th Elgin Regiment of the Canadian Militia, and was conscripted to the 1st (Western Ontario) Battalion in 1918. He transferred to the Royal Air Force and was sent to Deseronto for training but suffered injuries in an automobile accident that summer, followed by being bedridden by the influenza in the fall, both of which kept him from active service. He returned to St. Thomas to run his family’s onion farm.

At the outbreak of World War I, Hepburn had already enlisted in the 34th Fort Garry Horse but was unable to obtain his parents’ consent to sign up for the Canadian Expeditionary Force. He then became a lieutenant in the 25th Elgin Regiment of the Canadian Militia, and was conscripted to the 1st (Western Ontario) Battalion in 1918. He transferred to the Royal Air Force and was sent to Deseronto for training but suffered injuries in an automobile accident that summer, followed by being bedridden by the influenza in the fall, both of which kept him from active service. He returned to St. Thomas to run his family’s onion farm.

After the war, Hepburn joined the United Farmers of Ontario (UFO) helping to start its branch in Elgin County, but by the mid-1920s he switched to the Liberal Party. In the 1926 election, he was elected to the House of Commons of Canada as a representative of Elgin West, and was overwhelmingly re-elected in the 1930 election.

Later that year he became leader of the Liberal Party of Ontario. His support of farmers and free trade, and his former membership in the UFO allowed him to attract Harry Nixon’s rump of UFO Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) into the Liberal Party (as Liberal-Progressives). This and the Great Depression led to the defeat of the unpopular Conservative premier George Stewart Henry in the 1934 provincial election. His stance against the prohibition of alcohol allowed him to break the Liberal Party from the militant prohibitionist stance that had helped reduce it to a rural, Protestant south western Ontario rump in the 1920s.

As premier, Hepburn undertook a number of measures that enhanced his reputation as the practitioner of a highly vigorous style. In a public show of austerity, he closed Chorley Park, the residence of the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, auctioned off the chauffeur driven limousines that had been used by the previous Conservative cabinet, and fired many civil servants. To improve the province’s welfare, he gave money to mining industries in Northern Ontario and introduced compulsory milk pasteurization (in so doing, he has been credited with virtually wiping out bovine tuberculosis in the province). Breaking with the temperance stance of previous Liberal governments, Hepburn expanded the availability of liquor by allowing hotels to sell beer and wine.

In 1942, Hepburn resigned as premier, but retained his seat until 1945, when he retired to his farm, where he died of a heart attack in 1953. His funeral was attended by five former premiers, and Rev. Harry Scott Rodney observed in his eulogy: “You met him, you shook hands with him, you were warmed by his famous smile, and you heard him say, ‘I’m Mitch Hepburn’; and in a few minutes you were calling him Mitch, and you liked it, and you felt you had always known him.”

Hepburn was the f irst Liberal to become Premier since George William Ross, and was the last Liberal Premier to win two successive majority terms until Dalton McGuinty.

irst Liberal to become Premier since George William Ross, and was the last Liberal Premier to win two successive majority terms until Dalton McGuinty.

In 2008, the Thames Valley District School Board named a school after him in St. Thomas. The school is located only miles away from his family’s farm, Bannockburn Farms, it was officially opened in January 2009.

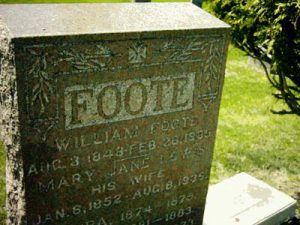

In 2007, the Ontario Minister of Culture announced funding for the Premiers’ Gravesites Program, delivered by the Ontario Heritage Trust, to mark and commemorate the gravesites of Ontario’s premiers. Specially designed bronze markers inscribed with the individual premier’s name and dates of service are installed at each gravesite, along with flagpoles flying the Ontario flag, where possible. This program is administered by the Ontario Heritage Trust with funding support from the Government of Ontario. The Trust is an agency of the government dedicated to identifying, preserving, protecting and promoting Ontario’s heritage for the benefit of present and future generations.